Moyne Abbey / The Monastery of Moyne

“The golden sun is sinking far

“The golden sun is sinking far

Beyond Kilcummin shore,

The pale faced moon of rosy June

Doth rise to waken lore;

The evening star illumines far

Around old Nephin’s crown,

And muffled roar of Rosses shore

Doth swell these valleys round;

This silent strand, these waters grand,

So deep, so lone, so blue;

This Abbey Moyne whereon I stand,

This prospect of Moyview,

The calm repose of evenings close

That wraps this pool of Moyne,

And wailing cry of seabirds high

Deep silence all enjoin.”

(Rev. James Greer)

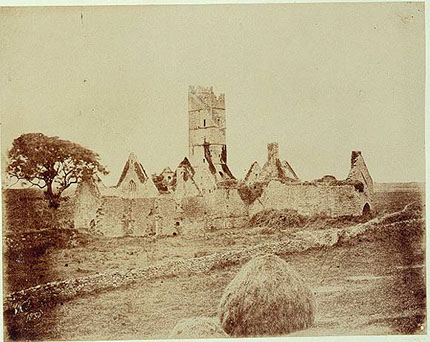

Situated in spectacular surroundings about 3.5 kilometres from Killala on the old Ballina or “French Road,” are the splendid ruins of the abbey of Moyne: ‘magnificent even in its wreck.’ This site has strong associations with St. Patrick and is mentioned by his biographers.

Situated in spectacular surroundings about 3.5 kilometres from Killala on the old Ballina or “French Road,” are the splendid ruins of the abbey of Moyne: ‘magnificent even in its wreck.’ This site has strong associations with St. Patrick and is mentioned by his biographers.

A large and skilled workforce was employed in the construction which began about 1455. Built in late Irish Gothic style for a branch of the Franciscans (Franciscans of the Strict Observance) by Mac William Burke (de Burgo) through the instrumentality of Nehemias Ó Donuchadha/Donoghue, the first Provincial Vicar in Connacht of the Order of St. Francis de Observantia -an entry in the Annals of the Four Masters confirms this.

The abbey stands on the site of an earlier oratory attributed to St. Muinchin/Mucna, a local folk-saint. He is reputed to have been a disciple of St. Patrick’s who ruled a church which is called Maighin; that he lived until about 520AD and that his birthday was celebrated at Moyne on the 4 March. Furthermore, some authorities claim that Moyne may even be the location of Máyva, as referenced by the geographer Ptolemy in the second century AD.

There is an extant theory which claims that the founder of the Abbey was one Thomas Oge Bourke of Moyne-Culeagh, who died McWilliam Oughter, and that O Donoghue, the Provincial, only took possession of the house by licence of Pope Nicholas V. In the course of 1460 a Papal Decree stated that “A single place in their Province (i.e. Friars Minor of the Observance) in Ireland was lately built, called Magyn, in the diocese of Killala, by the authority of letters of Nicholas V”.

“The edifice was large and well-constructed, and the gardens were surrounded by a strong wall. Within the cloister there was a spring from which the water was conveyed to various parts of the house, supplying the water needed for kitchens and workshops, and carrying off the sewage from the lavatories to the sea. The mill race on its way to the sea turned the wheels of two mills. There was never a shortage of water, and there was also an abundance of fish, rabbits and leguminous plants, while shell-fish were there for the picking along the shore...Large ships were able to come up as far as the infirmary at full tide.”

(L. Wadding, Annalis, Minorum, X111 Quaracchi, 1932)

According to a local legend reminiscent of the selection of the site of the church of ‘Sancta Maria ad Nives’ in Rome, the monks had their choice of all of the lands owned by their benefactor, and having examined several likely sites, O Donoghue, the Provincial, in the company of a Father Chilvart, settled on Moyne (Maighin translated as a small plain), apparently with the help of either a little robin or wren. The little robin was held in high regard by the Irish as this bird was said to have got its red breast through its efforts to stanch the blood on the brow of the crucified Christ. Conversely, the wren is a maligned bird as it was regarded as promiscuous, which would not have endeared it to the more puritanical of Christian preachers. Apparently the upright tail of the wren was viewed as sexual imagery, as was the black chafer, which raises its tail when threatened. The chafer (known in Irish as daradaol or deargadaol ) also had an anti-Christian representation as it was believed that it informed on Christ, thereby leading to His arrest.

According to a local legend reminiscent of the selection of the site of the church of ‘Sancta Maria ad Nives’ in Rome, the monks had their choice of all of the lands owned by their benefactor, and having examined several likely sites, O Donoghue, the Provincial, in the company of a Father Chilvart, settled on Moyne (Maighin translated as a small plain), apparently with the help of either a little robin or wren. The little robin was held in high regard by the Irish as this bird was said to have got its red breast through its efforts to stanch the blood on the brow of the crucified Christ. Conversely, the wren is a maligned bird as it was regarded as promiscuous, which would not have endeared it to the more puritanical of Christian preachers. Apparently the upright tail of the wren was viewed as sexual imagery, as was the black chafer, which raises its tail when threatened. The chafer (known in Irish as daradaol or deargadaol ) also had an anti-Christian representation as it was believed that it informed on Christ, thereby leading to His arrest.

In any case, the intervention of the robin was taken as a divine gesture, after which the Provincial exclaimed: ‘God has shown us and that is the site of our monastery,’ and further referred to the location as:

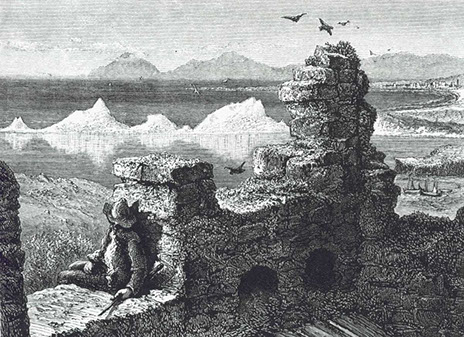

‘A sweet verdant plain crowning a gentle eminence, at whose foot the silvery Moy discharges its waters into the bay of Killala, right opposite a sandy ridge, called by the natives, the island of Bartragh or Bertigia.’

Completed in 1462, and consecrated by Donatus O’Connor-Sligo, a Dominican monk, and member of a noble family which gave more than one bishop to the See of Killala, it is told, Moyne was to rise to prominence within Irish Franciscan circles, with Provincial Chapters of the order being held there on several occasions between 1464 and 1550. At its zenith the monastery boasted a valuable library, infirmary, two mills for grinding corn, excellent pasturage, pools for fish, a water-mill and a never-failing spring of wholesome water. The community including priests, professors, students and lay-brothers, would have numbered upwards of 50.

Completed in 1462, and consecrated by Donatus O’Connor-Sligo, a Dominican monk, and member of a noble family which gave more than one bishop to the See of Killala, it is told, Moyne was to rise to prominence within Irish Franciscan circles, with Provincial Chapters of the order being held there on several occasions between 1464 and 1550. At its zenith the monastery boasted a valuable library, infirmary, two mills for grinding corn, excellent pasturage, pools for fish, a water-mill and a never-failing spring of wholesome water. The community including priests, professors, students and lay-brothers, would have numbered upwards of 50.

“In fact there was no commodity of life wanting to our Friars, as long as they were allowed to live peaceably in Moyne. Their gardens and orchard supplied them with vegetables and fruit, their ponds with fish, the beach with crustacea, and the island of Bertragh with succulent rabbits and as for wine, did not the Spanish caravals come freighted with it into the neighbouring harbour of Killala.”

(Rev. C. P. Meehan, The Rise and Fall of the Franciscan Monasteries and Memoirs of the Irish Hierarchy in the Seventeenth Century, 1869)

Church records inform us that the celebrated fifteenth-century Franciscan manuscript Meditationes Vitae Christii, was translated into Irish as Smaointe Beatha Criost, in the scriptorium of Moyne, by a choral canon of Killala named Tomás Gruamdha O’Bruacháin, and today, Moyne is regarded as one of the most impressive ecclesiastical ruins in the country and probably the finest example of a Franciscan ruin in Ireland. Even in the nineteenth century the place was spectacular as evidenced in the words of a contemporary chronicler who wrote: “The impress that Moyne Abbey left on me that day never passed away; and with great pleasure and sweet hallowed memories I have again and again visited the place, so grand, so solemn, so noble in its ruin.”

Hoary pile of crumbling glory,

Hoary pile of crumbling glory,

Moaning to the midnight breeze,

Sad to living men thy story-

Pride of bygone centuries:

Who alone the truth displaying-

Shadows of the wrecked and old-

Shuns the form of man decaying

Shuns the tale of ruin old.

Hie ye here the vain conceited;

Hie ye here the poor man’s foe;

Nobler forms the worms have treated

Mouldering in the vaults below.

(Dr Barrett)

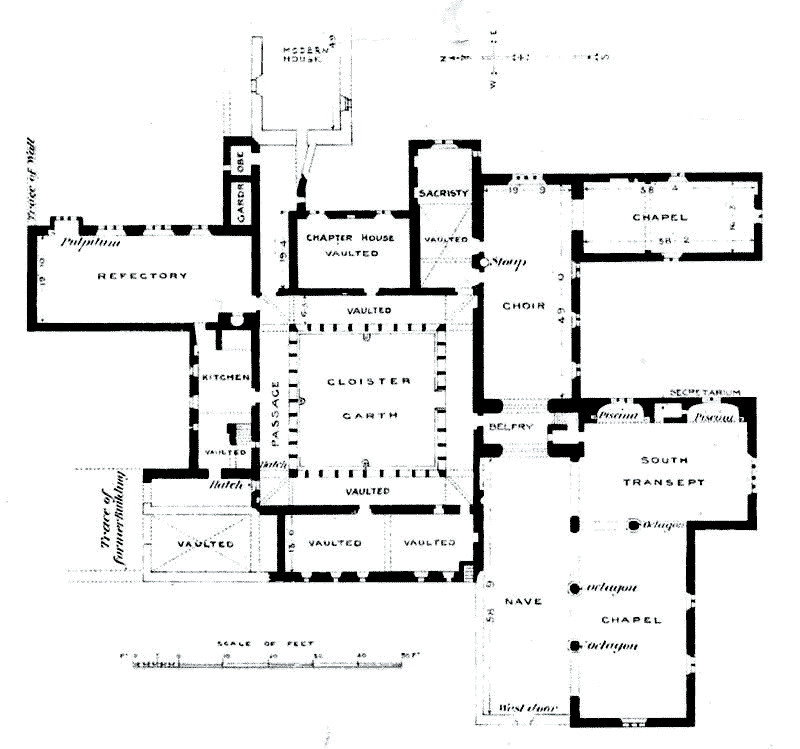

The church which occupies the whole of the south side includes nave, aisle, south transept, choir and chapel of the Blessed Virgin; it measures about forty metres by six metres, but is not of uniform width. Furthermore, it originally possessed a fine eastern window, and a once magnificent but still graceful tower. Complete with a cut-stone circular staircase of 101 perfectly slotted steps, the tower rises from high and broad arches to a height of about twenty-six metres, a marvellous monument to the men who fashioned it many centuries ago.

The tower stands upon the two gables between the choir and the body of the church, the arches being turned on consoles from east to west. Before insurance became such a consideration, one could access the tower and by means of the staircase reach the top, from where a spectacular and commanding view of Killala Bay and the surrounding countryside awaited. The cloister is built on plain pillars placed in couplets, just as they are at Sligo Abbey. East of the cloisters are the chapter house and refectory, while to the north, the kitchen house may be found. Traces of former buildings may also be seen on the north side.

The tower stands upon the two gables between the choir and the body of the church, the arches being turned on consoles from east to west. Before insurance became such a consideration, one could access the tower and by means of the staircase reach the top, from where a spectacular and commanding view of Killala Bay and the surrounding countryside awaited. The cloister is built on plain pillars placed in couplets, just as they are at Sligo Abbey. East of the cloisters are the chapter house and refectory, while to the north, the kitchen house may be found. Traces of former buildings may also be seen on the north side.

“The abbey is still almost perfect, except the roof and some buildings on the North side, which were taken down about 1750 by the then proprietor, Knox, to furnish materials for a dwelling house which was erected nearby...The church is 125’ long by 20’ broad towards the East; from the West door to the tower the breadth varies from 40’ to 50’; on the broadest space is a gable with a pointed window of stone and of fine workmanship. To the Eastern wall of this portion of the building were two altars, having a piscine to each; between the altars there is an arched recess, which would seem to have been a place of safety for the sacred utensils of the altars...On the right side of the aisle is a range of arches corresponding with the height of that tower, done in hewn stone; the arches, which are hexagonal and turned on consoles, support the tower, which is nearly in the centre of the church, and about 100’ in height. The ascent to the summit of the tower is by a helix of 101 steps”.

(Rev. Thomas Walshe, Ecclesistical History of Ireland, 1885)

It is claimed by some ancient authorities that considerable parts of the abbey were constructed from oolite, a local stone, so like marble and composed entirely of petrified sea-shells. What is no less remarkable, the mortar used in the building was made from burnt sea-shells, a fastener which was once thought to be ‘the most binding description of cement that can be found.’ Killala Round Tower is also constructed from oolite.

Despite its strict observant connections, the completed work was described as follows;

“The exquisite beauty of the architecture of both church and monastery was the theme of every tongue; and in the rich display of ornamentation in the tracery of the windows and the coupletted pillars of the cloister, even to this day, attest that the men who executed the work were thoroughly skilled in their craft, and enthusiastic cultivators of art in every departments.”

During the Tudor period, most especially during the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1 of England, the community at Moyne suffered greatly at the hands of the British military. It is related in the local tradition how a priest arrested and wrongfully charged with having knowledge of a plot against the Queen protested his innocence, but was still ordered to be hanged. The priest in question craved permission to be allowed to confess his sins to a friar of Moyne before being put to death. Permission was granted and in the aftermath, the priest was duly hanged (some accounts say from the bell-tower, the bell of which was said to have been a gift from the Queen of Spain) and the friar confessor exhorted by every means, in other words torture, to reveal the secrets of the confessional.

During the Tudor period, most especially during the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1 of England, the community at Moyne suffered greatly at the hands of the British military. It is related in the local tradition how a priest arrested and wrongfully charged with having knowledge of a plot against the Queen protested his innocence, but was still ordered to be hanged. The priest in question craved permission to be allowed to confess his sins to a friar of Moyne before being put to death. Permission was granted and in the aftermath, the priest was duly hanged (some accounts say from the bell-tower, the bell of which was said to have been a gift from the Queen of Spain) and the friar confessor exhorted by every means, in other words torture, to reveal the secrets of the confessional.

It is told that to help with the extraction of the information a rope was ‘tied about the victim’s head, forehead, and temple,’ and slowly tightened by the turning of a stout stick until ‘his eyes burst out, his brain was forced through his ears and his skull finally broken.’ Despite the best efforts of the torturer, the friar, named as John O’Dowd, nobly refused to reveal the confessional secrets and was also strung up from the self-same tower. Sometime after this occurrence, local accounts mention 1578/79, the community were advised of an impending military raid by the troops of Sir Edward Fitton and as a result, the community, with one exception, an aged lay-brother named Felix O’ Hara, who refused to leave, put to sea in their boats in order to make good their escape.

After some time the community returned to find the building plundered and the venerable old man lying dead in a pool of blood on the steps of the grand altar. Several years later, Father Donagh Mooney, the then Minister Provincial of the Irish Franciscans, who was on a visitation to Moyne at the time, happened to meet some of the soldiers who had taken part in the aforementioned atrocities. The soldiers attested to the truthfulness of the details as recorded by Mooney and begged his forgiveness.

Following years of persecution Moyne was confiscated and granted in 1595 at an annual rent of 5/- (five shillings) to Edmund Barrett, a native of Cork and favourite of Queen Elizabeth who was educated at the English court. This was only a tiny part of the vast amount of confiscated church lands which Edmund Barrett received in that year, for he also received lands in counties Kerry, Sligo, Galway, Roscommon and Leitrim. He subsequently sold the property to one Robert Harrison, who then sold it to Sir William Fenton, who it is told held a market at Moyne every Tuesday. In 1603 a patent was granted to Fenton for a market and two fairs lasting two days to be held on 25 August and 14 October. At this time just six friars were living rent free in some humble cells on the property. By 1806, two extra fair days, 18 May and 3 December, were added.

In 1635 the lands passed into the hands of Richard Boyle, Ist Earl of Cork, and in 1641 they were given to Sir Arthur Gore and termed “Protestant Lands” in the Survey of that year. After him came the Lindsays, a Cromwellian family and it is told in the local tradition that it was they who dismantled the friary, using gunpowder to remove the roof, and further compounded the ravages by selling off the ‘Great Bell of Moyne,’ as already mentioned, said to have been a gift from the Queen of Spain. The bell was sold for £700, a figure which gives some indication of its magnificence. About the year 1718, Moyne Abbey, with the lands including Bartra Island and the adjacent islands came into the possession of the Knox family, when Francis Knox (1682-1730), the eldest son of William Knox of Castle Rea of (Castle Rea stood at Palmerstown close by Killala) took up residence there on his marriage to Miss Dorothea Annesley of ‘Little Rath’, county Kildare.

In 1635 the lands passed into the hands of Richard Boyle, Ist Earl of Cork, and in 1641 they were given to Sir Arthur Gore and termed “Protestant Lands” in the Survey of that year. After him came the Lindsays, a Cromwellian family and it is told in the local tradition that it was they who dismantled the friary, using gunpowder to remove the roof, and further compounded the ravages by selling off the ‘Great Bell of Moyne,’ as already mentioned, said to have been a gift from the Queen of Spain. The bell was sold for £700, a figure which gives some indication of its magnificence. About the year 1718, Moyne Abbey, with the lands including Bartra Island and the adjacent islands came into the possession of the Knox family, when Francis Knox (1682-1730), the eldest son of William Knox of Castle Rea of (Castle Rea stood at Palmerstown close by Killala) took up residence there on his marriage to Miss Dorothea Annesley of ‘Little Rath’, county Kildare.

This branch of the Knoxes were mentioned as being ‘a gentler and kindlier family, who never acquired a character for bigotry or sectarian intolerance.’ In 1838, Charles Kirkwood R.N. married Henrietta, the second daughter of one William Henry Knox, a descendant of the aforementioned Francis Knox and as a result of the marriage he was able to acquire the lands of Bartra and Moyne. The lands remained in the Kirkwood family until about 1948 when they were taken over by the land Commission and the buildings by the National Monuments Commission.

There are extant records which show that some members of the local noble clans including O’ Dowds and Bourkes were buried in the friary previous to its suppression. In the side-chapel to the right, or Epistle side of the high altar, there are two slabs in the side-walls, one marked “D” and the other marked “B,” which probably indicate the burial places of the O’Dowd and Bourke families respectively. It is known for sure that Owen O’ Dowd, clan chieftain for more than thirty years was buried here in 1538, having spent the closing years of his life as a lay-brother. McFirbis informs us that another Owen O’Dowd, who ruled as chieftain for seven years was also buried here in 1545, alongside his wife, Sadhbh or Sabia, the daughter of Walter Bourke.

To the right of the door leading to the tower stair-way lies another doorway, now closed off by a burial slab in memory of Mathew Bellew. To say that Bellew was a colourful character would be doing him an injustice. His date of death is given as 3/3/1797, whereas in actual fact he was hanged at Killala in September 1798, for his part in the Rising of that year. In the same unmarked grave lie the remains of his brother, Dominick Bellew, Catholic Bishop of Killala, who died as a result of a fall from his carriage in 1812. It is told that his horses took flight in Killucan, county Westmeath, as he was making his way home from a Bishop’s Meeting in Dublin. Their father may also be buried here in the abbey. The original tomb of the Bellews fell into decay and it was once referenced in the following way “for a long period the remains of the prelate and his brother could be discerned through the aperture in the wall. At the repairing of the abbey they were interred in the floor beneath.”

To the right of the door leading to the tower stair-way lies another doorway, now closed off by a burial slab in memory of Mathew Bellew. To say that Bellew was a colourful character would be doing him an injustice. His date of death is given as 3/3/1797, whereas in actual fact he was hanged at Killala in September 1798, for his part in the Rising of that year. In the same unmarked grave lie the remains of his brother, Dominick Bellew, Catholic Bishop of Killala, who died as a result of a fall from his carriage in 1812. It is told that his horses took flight in Killucan, county Westmeath, as he was making his way home from a Bishop’s Meeting in Dublin. Their father may also be buried here in the abbey. The original tomb of the Bellews fell into decay and it was once referenced in the following way “for a long period the remains of the prelate and his brother could be discerned through the aperture in the wall. At the repairing of the abbey they were interred in the floor beneath.”

In1690 a chieftain of the aforementioned O’ Dowd clan was present at the Battle of the Boyne fighting on the side of King James against the forces of William of Orange. Another was slain at the Battle of Aughrim 1691, fighting in the army of Marshal St. Ruth, also against the Williamites. It is maintained that this particular warrior fell with his sword strapped to his wrist. There is a legend attached to his death which tells that when the body of this gallant soldier was located on the field in the aftermath of the contest, his wrist was so badly swollen from his many exertions that the sword had to be cut free from his hand. The two warriors, both of whom were reputed to have been over seven feet tall, lie buried at Moyne Abbey. Many years later, when a fresh grave was being dug in the Abbey grounds close by the spot where the warriors were buried, two skeletons were revealed, both measuring over seven feet long.

Moreover, it is also told that William O’Ceardaigh, a celebrated friar of Moyne who is described in the Annals of Lough Cé as “the best preacher in Ireland” died in the Abbey in 1586, and lies buried there.

What follows is an account written by a writer known only by his initial J.C. following a visit to Moyne in 1793:

“The Abbey itself is almost perfect, except the roof and some buildings on the north side, which were taken down about forty or fifty years ago, by the proprietor, to furnish materials for a dwelling house which was erected nearly on the site of the old walls and joined the church...The sacrilegious had that had done this, I was told by the country people, never came to any good after, nor any of those who had been concerned with it. Certain it is the house was but a short time inhabited and is now completely in ruins.” The writer then goes on to muse whether Time, which had dealt so relentlessly with the new building, had not, as it were, taken pity on the original edifice, which was once the seat of piety and learning, and preserved it from decay.

“The Abbey itself is almost perfect, except the roof and some buildings on the north side, which were taken down about forty or fifty years ago, by the proprietor, to furnish materials for a dwelling house which was erected nearly on the site of the old walls and joined the church...The sacrilegious had that had done this, I was told by the country people, never came to any good after, nor any of those who had been concerned with it. Certain it is the house was but a short time inhabited and is now completely in ruins.” The writer then goes on to muse whether Time, which had dealt so relentlessly with the new building, had not, as it were, taken pity on the original edifice, which was once the seat of piety and learning, and preserved it from decay.

(Anthologia Hibernica, 111, January 1794)

On the west gable of Moyne, either side of the main doorway, and also on the adjoining sidewall, a large number of unique crudely carved images of ships may be found. The ‘Moyne Ships’ as they are sometimes called, were only uncovered when the various layers of plaster began to peel as a result of age and weathering. Images of ships are also to be found etched on bricks at the Carmelite Friary of Elsinore, in Denmark, like Moyne a riparian location.

On the west gable of Moyne, either side of the main doorway, and also on the adjoining sidewall, a large number of unique crudely carved images of ships may be found. The ‘Moyne Ships’ as they are sometimes called, were only uncovered when the various layers of plaster began to peel as a result of age and weathering. Images of ships are also to be found etched on bricks at the Carmelite Friary of Elsinore, in Denmark, like Moyne a riparian location.

Professor McAllister of the R.S.A.I. first noticed the Moyne images in 1939, and subsequently in 1943, he made his own drawings, before publishing them with a detailed report in the Journal of the Society. The Professor maintains that the images were made during the building of the Abbey, at a time when Irish hopes of Spanish aid were running high, but they were covered and concealed after 1583, possibly 1588. Another theory suggests that they were possibly a “jeux d’esprit” by the plasterer and made to provide a bond for the final coat of original plaster, probably created by a friar or lay-brother who was familiar with ships and their riggings, but this is mere conjecture. Nonetheless, McAllister suggested that one of the ships bore a striking resemblance to the Arke Royall, Queen Elizabeth’s flagship.

Professor McAllister noted “…it does not seem possible that plasterers employed in plastering the interior of a church would be permitted to diversify the task for which they were engaged in a way which did not in any way improve its appearance. Surely such proceedings would not be tolerated. And moreover the figures seem to me to have been made in plaster already dry-cut or pocked, not pressed, as they would have been had the plaster been damp and soft…I cannot but think that the Moyne Ships, as they may be called, form a document of social history of considerable interest.”

Professor McAllister noted “…it does not seem possible that plasterers employed in plastering the interior of a church would be permitted to diversify the task for which they were engaged in a way which did not in any way improve its appearance. Surely such proceedings would not be tolerated. And moreover the figures seem to me to have been made in plaster already dry-cut or pocked, not pressed, as they would have been had the plaster been damp and soft…I cannot but think that the Moyne Ships, as they may be called, form a document of social history of considerable interest.”

It is noticeable that the present doorway is not the original but a later insertion, probably from the seventeenth century. Professor McAllister suggested that the original doorway was probably flat-topped, and spanned either by a lintel or by a very low-centred arch, and during its insertion the wall was cut to fit the new jambs and some of the plaster art cut in the process.

In July, 1943, McAllister gave a talk to the Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland in Cork-the talk was titled ‘On graffiti representing ships on the wall of Moyne Priory, Co. Mayo.’ This was his explanation:

“In 1588 the invincible Armada set sail from Lisbon. We can believe that the unhappy inmates of Moyne, who were suffering many hardships, founded high hopes on the success of the enterprise; and prepared themselves to celebrate the expected victory, which would restore to them and to their brethren all that they had lost by means of a great historical painting to record for centuries the downfall of their enemy and their own emancipation.”

(R.A.S. McAllister, R.S.A.I. Jr., LX111, 1943)

The land on which the monastery stands was the site of the Great Battle of Moyne, when in 1281, the natives under William Fionn of Cill Comain or William Mór of Moyne (as he was later known) defeated the Normans, under the command of Adam Cusack. It was also known as ‘Moyne of Kilroe,’ from the small ancient church the remains of which are situated on a small hillock to the northwest. Both the church and battle are referenced on this site.

“In mendicant orders-Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Augustinians-monastic life and outside religious activity are combined; neither personal nor community tenure of property are allowed under their original regulations. They shared the characteristics outlined above but were individually distinct owing to such factors as the founder’s influence, the rules of the order and the particular focus that each adopted in their work. Indeed, the orders were also distinguished by the colour of the habits their brethren wore. Commonly held, however, was a belief in combining prayer and devotion with preaching and pastoral work in the community. Under their rule of poverty the friars would beg for alms to sustain themselves.”

“In mendicant orders-Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Augustinians-monastic life and outside religious activity are combined; neither personal nor community tenure of property are allowed under their original regulations. They shared the characteristics outlined above but were individually distinct owing to such factors as the founder’s influence, the rules of the order and the particular focus that each adopted in their work. Indeed, the orders were also distinguished by the colour of the habits their brethren wore. Commonly held, however, was a belief in combining prayer and devotion with preaching and pastoral work in the community. Under their rule of poverty the friars would beg for alms to sustain themselves.”

(Yvonne McDermott, Returning To Core Principles, History Ireland Jan/Feb 2007)

At the time of its zenith the friars of Moyne figured in a satirical poem by a poet named as Aengus O’Dalaigh-Daly-‘Angus of the Satires.’ It is told that the poet’s pay for composing a poem of such ‘due derision’ and ridicule of his fellow countrymen may have been substantial, but unfortunately for him, the risk proved much greater, and he was eventually slain in 1617 by a servant of a chieftain who smarted at his poetic lash. One extant translation is as follows:

‘The friars of Moyne give you wormwood enough

But that’s rather fancy, uneatable stuff

Still they’ll feed you, that is, if you’re handy at filling

Your inside with cakes thick and big as a shilling

‘I don’t understand them; they never may sigh

For the flesh-pots of Egypt, but why should not I

Let the priest, if he pleases, fast himself like Brahmin

But he’s really too kind if he kills me with famine!

“The Abbey of Moyne, situated on the estuary of the River Moy, is certainly one of the noblest of the Franciscan Abbeys in Ireland. It is two miles from Killala, six miles from Ballina on the old road by the river. It is barely one-eighth of a mile from the public road, yet on entering its precincts its loneliness, its solitary air and surrounding, is the first impression produced. The Still ‘Pool,’ as the arm of the Moy beneath is called, the solemn tower, casting its long shadow over the countless graves and tombs, the stillness of the luxurious fields around, where the silent cattle graze, but where man is not seen, the rising or ebbing flow of the Moy scarcely making a ripple on the sweet strand, all without a sound, give the first impression as utter loneliness. One is at once forced to feel that here was a fit place for a Community to live away from noise, from care, from the tramp and traffic of the world’s ways, to have thoughts fixed on the quiet and “rest that remaineth for the people of God.”

(The Windings of the Moy, Rev, James Greer)

The Moyne Chalice: Bearing the inscription “Rickard? McDonagh me fiery et? Dare fecit in usu Conventyale Moyn. A.D. 1670” on the ancient base (the cup is of more recent make) the “Moyne Chalice” is now held in St. Muredach’s College, Ballina.

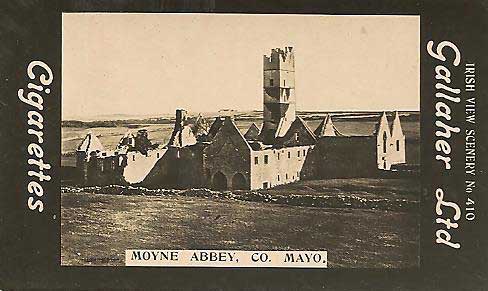

In the early part of the twentieth century (1908 and 1910), Gallaher Ltd, Belfast issued a high profile, numbered photographic cigarette-card collection titled “Irish View Scenery.” The photographer was the celebrated Robert John Welch, the official photographer for Harland and Wolff, and the images captured and documented scenes throughout the entire island of Ireland. Moyne Abbey was featured as card number 410.

In the early part of the twentieth century (1908 and 1910), Gallaher Ltd, Belfast issued a high profile, numbered photographic cigarette-card collection titled “Irish View Scenery.” The photographer was the celebrated Robert John Welch, the official photographer for Harland and Wolff, and the images captured and documented scenes throughout the entire island of Ireland. Moyne Abbey was featured as card number 410.

Two Pieces of Moyne “Ghostlore”

The old people of Killala and its environs always maintained that at one time there were two side rooms in Moyne Abbey, both filled with bones and skulls, giving an impression, as one ancient citizen of the region mused ’that it was a grand, silent mouldering mansion of the dead where the great and the grand with the poor and simple mouldered together...There were kings and councillors of the earth which built desolate places for themselves, and princes that had gold and filled their houses with treasures, the poor, the infirm, the weak, the despised, the newly born and infants that never saw the light.’

In any case, the story goes that one night all the bones were shipped off by schooner to be ground into manure, and as the old people used to say, ‘thus more quickly to bring earth to earth and ashes to ashes.’ This practice was not uncommon in the Ireland of long ago, and it is one most especially associated with monasteries situated on the coast. According to the tale, the heavily –laden sacrilegious schooner was still in sight of land when she sank with all hands.

“Having viewed all that I thought was likely to interest me in this fine ruin, I was proceeding in company with my guide to take my departure when on lifting up a skull somewhat remarkable for the bumps developed on its surface, and which of course would have been a good subject in the hands of a phrenological lecturer, and as is in this respect valuable, and likely to be abstracted by some curious person, I asked were the people disposed to come near the Abbey by night?

“Och then yer honour, there’s not a man in the barony, no not his reverence the priest himself would come here in the dark, for there be the terribleist noises by night here, that ever mortal man heard. People in the broad day, and when they can afford as I may say, to be stout, tell you that its only owls and wild cats, but them that knows it, hould out for it, that its one of the ancient friars. I’m sure myself forgets his name, though I once heard it. But he broke his vow, sold his soul to the devil, and in the midst of his devilry was drowned crossing the river Moy. Anyhow, the noises are heard as sure as anything. And now as we’re leaving the place I’ll tell yer honour a story as thrue as you’re there:-

Not many years ago there was a set of jolly boys one night drinking and carousing in Killala, and amongst the rest was Peter Cumming, the chapel clerk. Now, when they were all pretty well I thank you, they all got valiant intirely, and one said he wouldn’t be afeard to do this and another swore he had done, and would again do that. ‘I’ll tell ye what I’ll do’, says Peter, ‘I’ll bet any one a golden guinea and here it is under me hand on the table, that I’ll go this very hour to Moyne Abbey and bring here a skull out of it in my pocket handkerchief, and lay it down on this table.’ So all thinking it was an impossible thing-that no man alive would dare to go for to do such a thing-to put an end to Peter’s brag, sure and certain it was only boastin he was, they all said done to the wager and Peter’s golden guinea was covered in a moment with twenty-one white shillings. So Peter for his courage sake and the money, and besides having the spirits in him, sets off for the Abbey-and troth I don’t envy the scape-grace as he went whistling along, putting out of him the wind, as a body may say, to give the more room for his courage. And now my joker gets near the place and he sees the tower lifting its tall self and cutting on the sky and one star bright entirely is sparkling like a cat’s green eye, just over yonder pinnacle where the sea-eagle now and then comes and sits…Still Peter’s bravery was not put aback-there was as yet no occasion-all was silent in the air, on the land, and out at sea, except now and then comes the dash of the swelling tide as the easy wave came in and shattered the foam amongst the shore pebbles. And now Peter passes the door, which as you see lies continually open, and he has no light to guide him except one or two stars that sent down but a cold, green, good-for-nothing twinkle-the walls and the ivy darkening more and more all around. So he turns to the right, and down he goes on his hands and knees, and he makes to the very spot where you and I now stand, creeping on and on, for he knew right well that in the corner forenenst you, there was, as there is now, a heap of skulls. Yer honour, wasn’t the mad fellow morthal brave? Well he gropes and gropes for a skull, and he has just got a grip of one, and is fumbling in his pocket for his handkerchief to tie it up in, when he hears all at once a slow sickly voice, half groan, half growl, as a body may say-just what you’d hear from a dying crathur that was saying his last words, with the rattles in his throat; and this was what was said-‘Och Peter Cumming, you bad bad boy, what’s this you’re about? Bad luck to ye! What are ye doing with me skull? With that, up rises Peter, his hands off the ground, but still standing on his two knees and sure enough he was all of a trimble, and well he might; for looking towards that very corner now before us, he saw what he had reason to remember to his dying day; for there stood his own grandfather Padraig Cumming surrounded by a light that came of a blueish colour, from out of the earth, like what comes in September out of the reeds along the river; and there old Padraig stood just as he was before his last sickness, in his frieze coteen and his sheepskin breeches all smoth and greasy, and his bay-wig, and the very tobaccy running down from the two corners of his mouth, and staining all his rough chin. ‘Heaven’s rest be with you Padraig, but there ye wor the picthur of what you looked the week before the death sickness came on ye.’ ‘Och then Pethereen (sez the ghost, for it was nothing else) ye unlucky boy, what brings ye here, and what are ye doing with me skull? What for would ye have your grandfather stand up at the day of judgement without a head, ye divil-may-care, drunken irreligious blackguard? Now, all this while that the grandfather was scolding, Peter was a getting up off his knees, and as the ould fella kept on abusing without killing him, he takes courage and he ups and says to the ghost ‘Ah then grand daddy dear, is that yourself? And why are ye walking and what makes ye unquiet? Maybe its masses ye want for yer poor sowl and sure I’m a good warrant to get them sed for ye; for I’m the chapel-clerk, and it will go hard with me if I don’t coax his reverence to say a dozen or two for ye, besides always keeping you in his intintions. And now, daddy dear, don’t be angry’, says Peter in a voice right sweet and coaxing, ‘don’t alanna grudge me the use of yer skull just for one bit of an hour, while I make a guinea out of it, sure its not every night a poor fellow the likes of me can turn a penny this way. Stay then, where you are till I come back; I’ll be here in no time and I’ll lave the skull, God bless it, just where I found it, and daddy dear, I’ll tell ye whats more, I’ll do if it be plasing to you, now that I know for sartin it is part of yourself, and that you can’t do without it at the day of Judgement, I’ll come here tomorrow and put it under the clay in the very spot where father and mother are buried, and who I myself will be put when I.m buried, glory be to God and won’t that plase you? Do heavens rest attend you and don’t say against my having an hour’s loan of your skull. With that Pethereen cast a fond but fearful look towards his grandfather, but now he saw nothing, the light was gone, nothing was to be seen but darkness, no sound but the wind sighing through the ivy leaves. ‘Silence gives consint’, says Peter, so tying up with two good knots the skull in his handkerchief, home he comes by the way he went, finds his company still drinking, lays down his skull before them and gets his guinea:- for I’d be glad to know who dare refuse or say he had not won his wager; seeing as how Peter proved his courage, and would stand up before any of them, when he had just been after facing a ghost. It is said that Peter was as good as his word and kept his promise to his grandfather’s ghost, for he did bring back the skull, and did put it decently under the clay where its resting for aught I know, to this very day. Some people to be sure were slow of believing that Peter saw his grandfather’s ghost at all, and that it was only a drunkard’s boast; for its but two thrue that Peter though chapel-clerk, was a great drunkard and a great liar to his dying day. But this is sartain, that a man for a wager brought away by night a skull from this Abbey and brought it back again which is what I would not do for all the guineas in Connaught!”

Not many years ago there was a set of jolly boys one night drinking and carousing in Killala, and amongst the rest was Peter Cumming, the chapel clerk. Now, when they were all pretty well I thank you, they all got valiant intirely, and one said he wouldn’t be afeard to do this and another swore he had done, and would again do that. ‘I’ll tell ye what I’ll do’, says Peter, ‘I’ll bet any one a golden guinea and here it is under me hand on the table, that I’ll go this very hour to Moyne Abbey and bring here a skull out of it in my pocket handkerchief, and lay it down on this table.’ So all thinking it was an impossible thing-that no man alive would dare to go for to do such a thing-to put an end to Peter’s brag, sure and certain it was only boastin he was, they all said done to the wager and Peter’s golden guinea was covered in a moment with twenty-one white shillings. So Peter for his courage sake and the money, and besides having the spirits in him, sets off for the Abbey-and troth I don’t envy the scape-grace as he went whistling along, putting out of him the wind, as a body may say, to give the more room for his courage. And now my joker gets near the place and he sees the tower lifting its tall self and cutting on the sky and one star bright entirely is sparkling like a cat’s green eye, just over yonder pinnacle where the sea-eagle now and then comes and sits…Still Peter’s bravery was not put aback-there was as yet no occasion-all was silent in the air, on the land, and out at sea, except now and then comes the dash of the swelling tide as the easy wave came in and shattered the foam amongst the shore pebbles. And now Peter passes the door, which as you see lies continually open, and he has no light to guide him except one or two stars that sent down but a cold, green, good-for-nothing twinkle-the walls and the ivy darkening more and more all around. So he turns to the right, and down he goes on his hands and knees, and he makes to the very spot where you and I now stand, creeping on and on, for he knew right well that in the corner forenenst you, there was, as there is now, a heap of skulls. Yer honour, wasn’t the mad fellow morthal brave? Well he gropes and gropes for a skull, and he has just got a grip of one, and is fumbling in his pocket for his handkerchief to tie it up in, when he hears all at once a slow sickly voice, half groan, half growl, as a body may say-just what you’d hear from a dying crathur that was saying his last words, with the rattles in his throat; and this was what was said-‘Och Peter Cumming, you bad bad boy, what’s this you’re about? Bad luck to ye! What are ye doing with me skull? With that, up rises Peter, his hands off the ground, but still standing on his two knees and sure enough he was all of a trimble, and well he might; for looking towards that very corner now before us, he saw what he had reason to remember to his dying day; for there stood his own grandfather Padraig Cumming surrounded by a light that came of a blueish colour, from out of the earth, like what comes in September out of the reeds along the river; and there old Padraig stood just as he was before his last sickness, in his frieze coteen and his sheepskin breeches all smoth and greasy, and his bay-wig, and the very tobaccy running down from the two corners of his mouth, and staining all his rough chin. ‘Heaven’s rest be with you Padraig, but there ye wor the picthur of what you looked the week before the death sickness came on ye.’ ‘Och then Pethereen (sez the ghost, for it was nothing else) ye unlucky boy, what brings ye here, and what are ye doing with me skull? What for would ye have your grandfather stand up at the day of judgement without a head, ye divil-may-care, drunken irreligious blackguard? Now, all this while that the grandfather was scolding, Peter was a getting up off his knees, and as the ould fella kept on abusing without killing him, he takes courage and he ups and says to the ghost ‘Ah then grand daddy dear, is that yourself? And why are ye walking and what makes ye unquiet? Maybe its masses ye want for yer poor sowl and sure I’m a good warrant to get them sed for ye; for I’m the chapel-clerk, and it will go hard with me if I don’t coax his reverence to say a dozen or two for ye, besides always keeping you in his intintions. And now, daddy dear, don’t be angry’, says Peter in a voice right sweet and coaxing, ‘don’t alanna grudge me the use of yer skull just for one bit of an hour, while I make a guinea out of it, sure its not every night a poor fellow the likes of me can turn a penny this way. Stay then, where you are till I come back; I’ll be here in no time and I’ll lave the skull, God bless it, just where I found it, and daddy dear, I’ll tell ye whats more, I’ll do if it be plasing to you, now that I know for sartin it is part of yourself, and that you can’t do without it at the day of Judgement, I’ll come here tomorrow and put it under the clay in the very spot where father and mother are buried, and who I myself will be put when I.m buried, glory be to God and won’t that plase you? Do heavens rest attend you and don’t say against my having an hour’s loan of your skull. With that Pethereen cast a fond but fearful look towards his grandfather, but now he saw nothing, the light was gone, nothing was to be seen but darkness, no sound but the wind sighing through the ivy leaves. ‘Silence gives consint’, says Peter, so tying up with two good knots the skull in his handkerchief, home he comes by the way he went, finds his company still drinking, lays down his skull before them and gets his guinea:- for I’d be glad to know who dare refuse or say he had not won his wager; seeing as how Peter proved his courage, and would stand up before any of them, when he had just been after facing a ghost. It is said that Peter was as good as his word and kept his promise to his grandfather’s ghost, for he did bring back the skull, and did put it decently under the clay where its resting for aught I know, to this very day. Some people to be sure were slow of believing that Peter saw his grandfather’s ghost at all, and that it was only a drunkard’s boast; for its but two thrue that Peter though chapel-clerk, was a great drunkard and a great liar to his dying day. But this is sartain, that a man for a wager brought away by night a skull from this Abbey and brought it back again which is what I would not do for all the guineas in Connaught!”

(Caesar Otway, Sketches in Erris and Tyrawley, 1841)

Two Moyne Poems

The Abbey of Moyne

The golden sun is sinking far

Beyond Kilcummin’s shore,

The pale-faced moon of rosy June

Doth rise to waken lore;

The evening star illumines far

Around old Nephin’s crown,

And muffled roar of Rosses shore

Doth swell these valleys round;

This silent strand, these waters grand,

So deep, so lone, so blue;

This Abbey Moyne whereon I stand,

This prospect of Moyview,

The calm repose of evening’s close

That wraps this pool of Moyne,

And wailing cry of seabirds high

Deep silence all enjoin.

What fitful moans along these shores

Creep o’er the brooding soul;

What weird sounds around these mounds

‘Mid awful silence roll?

They’re not the sounds of evening breeze

That hush the silver Moy;

They’re not the sounds of breaking seas

That stir a silent joy;

They’re not the sounds of surging wave

On Bartra’s lonely isle,

Nor rippling waves that sweetly lave

Old Connor’s ancient pile.

The sounds are those of awful dread

That through these arches steal,

The breathings of the myriad dead

That all these vaults conceal.

What thoughts arise as evening skies

O’ershadow this lone Moyne?

What mood of prayer, what deep despair,

What silence all enjoin!

Here monks did read their psalms and creed,

There friars knelt to pray;

Here Abbots ruled, these Priests were schooled

Within these cloisters gray;

Here scribes did write and burnished bright

Their writings all in gold;

There low and deep in yon dark keep

Died recreants of the fold;

Here loud refrains, and anthem strains

‘Mid Ave Maries rose,

At dawning light of summer bright

And winter evening’s close.

Most ancient pile, most holy shrine,

My heart around you deeply twines;

My prime is past, my days are flown,

My playmates gone to other climes;

Some in the deep for ever sleep

And some in battlefield did fall,

Some lie beneath an Indian sky

And some within this vaulted hall;

Not one remains to interchange

The greeting words of welcome home,

Not one to sing these simple lays

Who erst along this shore did roam.

But clear you speak in speechless tone

And tell the tale of other days;

Here you stand, my friend, alone

To welcome me from distant seas.

All praise to thee, MacBurke, must be,

Who reared this temple grand;

All praise to thee, o’er land and sea,

All praise o’er Awley’s land.

Amid the fray on battle day,

When passed by lingering fight,

‘Tis said you swore for Faith and Rome

To build this Abbey bright.

All bright you built of Oolite stone

Those gorgeous windows grandly tall;

The nave, the transepts, chancel floor,

And winding stair, the strength of all.

All chissled grand, all deeply planned,

These pointed gables, arches four,

And tower tall that ne’er shall fall,

But solemn stands o’er sea and shore.

Farewell old Abbey, long farewell,

I never more may feast mine eyes

On all the beauties of thy dell

Nor breathe the air of native skies;

Adieu loved prospect, long adieu

To haunts of childhood far and wide;

Scurmore, and Iceford and Moyview,

And Castleconnor poor in pride;

Adieu ye waters deep and lone

Where Humbert rode his fleet of sail,

And boomed his cannon o’er Coonmore

To raise the hopes of Erin’s Gael.

Adieu Killala’s ancient shrine

And tower round o’er Awley’s cave,

Where oft I knelt in childhood’s prime

And conned the text great Collins gave.

(Rev. James Greer)

Moyne Abbey

Before the River Moy was changed to flow by Enniscrone

Franciscan monks from other lands, their abbey had o’erflown

And seeking ground on which to build for their increasing band

An Abbey new, they travelled thro the whole of Awley’s land.

This site of Moyne they choose at last not far from old Rosserk

Where they received free gifts of land from one McWilliam Bourke

He undertook the building too, and labour freely gave

Of horses, carts and skilful men to build and to engrave.

No labour did they spare nor cost, upon this church of Moyne

Completely built of oolite stone from quarries which adjoin.

The workmanship and beauty was the theme of every tongue

While in a tower ninety feet a sweet-toned bell was hung.

The Bishop of Killala then, O’Connor journeyed there

In 1462 to consecrate the place to prayer.

From that for o’er a hundred years Moyne was a famous school

Where priests and scholars came to learn and abbots rose to rule.

A home where weary strangers found rest, food and comfort warm

And ships within the pool of Moyne might shelter from the storm.

Alas, in 1581 the dissolution came

When monasteries far and wide went up in smoke and flame

And Moyne the fate of others shared, its greatness could not save

What cared the English how much good it to the country gave.

A company of Fitton’s troops the Abbey sacked one night

Though warned by kindly friends the monks had safety sought in flight.

All fled to sea, save one old man, O’Hara, brave who swore

To stay and guard the sacred place or leave it nevermore.

Alas, when later those who fled dared venture back again

They found upon the altar steps O’Hara’s body slain.

They saw upon the floor his blood, shed by those ruthless bands

And elsewhere beheld the wreck of sacrilegious hands.

Ere two years passed they came again and fearsome tales were told

Of how the monks were treated by those warriors of old.

One friar they believed to be concerned in some dark plot

And put him to the torture to confess he knew not what

Then to the gallows he was dragged where one last wish he craved

That he might a confessor have so that his soul be saved.

This boon was granted with the hope the priest would then reveal

The secret which the soldiers thought the other did conceal

But he would break no sacred trust nor any secrets tell

And when the torture failed to force they hanged him up as well

Such deeds, as this, were common in those days of long ago

And every house in Erin told the same sad tale of woe.

In later years a Spanish ship cast anchor in the bay

And seeking bones to make manure took all they could away.

The famous bell and other things they stole and forth did flee

But lo, the hand of justice smote that ship upon the sea.

A storm arose and drove her on the rocks along the shore

And down she went with all her crew and all her grisly store.

No wreckage of that evil ship was ever seen again

Nor bodies of the crew who robbed the holy place in vain.

The sweet-toned bell went down as well and never more was found

It lies beneath the ‘pool’ they say and in a storm will sound.

The Abbey fell to ruin then for as the years rolled on

Its persecuted friars fled to safety one by one.

Behold the grand old ruin now, all open to the sky

Yet showing in its crumbling walls the shell of days gone by.

The lofty tower safe remains and still is worth a climb

To view the prospect from the top as monks in olden times

O’er Bartra Island, Enniscrone, Kilcummin and the sea

To Poullaheeney, Knocknarea, Killala and Rathlee.

Save that by Moyne the silver Moy has long since ceased to flow

The view is much the same today as centuries ago.

Though monks and river both have gone and taken trade away

The Abbey yet still stands sentinel o’er all Killala Bay.

And so may stand for endless years in lonely silence dumb

To tell the story of the past in ages yet to come.

(Written by C. A. St. George Knox of Palmerstown, Killala, December,1936)

View these photos in a gallery